For more than a decade I studied my spiritual path under a teacher whom I’ve named and honored and cited frequently enough. I was drawn to them in particular because I was seeking discipline, structure, and accountability in my path, and those were qualities for which they were famous.

During my time in study, however, occasionally I would ask questions or communicate what I thought was an expectation of my practice and my teacher would gently chide me. One treasured moment was hearing, “Tony, you don’t always have to work so hard.”

I remember one time we had a one-on-one check in about my practice and they gave me a piece of feedback that I cannot remember with complete accuracy but it was along that theme. The specifics of the wording may be less important than the message I received, though I hesitate to attribute my interpretation to them in case we had two different conversations.

Caveats named, what I remember was them expressing that I held my spiritual practice with a kind of rigidity and devotion that at some point would no longer serve me, and I would eventually need to let go of it.

Whatever they were seeing in that exact moment, I find myself thinking back to that frequently. In 2016 I felt myself approaching a peak of fervor, holding myself to impossible ideals and naturally falling short. Becoming fully self-employed forced me to face the limits of my idealism around, for example, money and labor.

Like many mental health therapists motivated by care for others and outrage at injustice, I wanted to be accessible to a wide range of people with varying incomes—but then I had to reconcile that longing with the reality of needing money for myself, my family, my needs, my goals. It became harder to take refuge in the joy of serving a higher purpose when I could not afford to take a vacation, for example, or imagine planning for retirement.

A part of me still has internalized the Catholic injunction to become a saint, an exemplar of virtue who shows humanity what it is capable of. When I was younger, I felt my failure to become a saint was a sign of my intrinsic awfulness. At this stage in my life, I now appreciate that saints are rare because that life is incredibly taxing. I further appreciate how many saints could only accrue the spiritual and internal force necessary to hold that virtue by renouncing other paths such as marriage, family, career, or living in the society of their time.

There is a spiritual path of living in the world and cultivating one’s soul and being, and it’s been known in many religions and cultures. Gurdjieff called it the Fourth Way, but I think of it as the path of the Red Mage—in the original Final Fantasy video game series, the Red Mage had some skill in fighting and some skill in general magic but mastery of neither.

That is the path I walk, and in walking the path I find these moments of feeling the costs of not committing to one or the other. A part of me dreams of the monastic life of solitude and devotion to spirit and my awakening, while another part of me wonders what would have been possible if I’d dedicated my considerable discipline and willfulness toward accruing money and power in this world.

All of this to say, even before the COVID-19 pandemic I was personally forced to look at all the ways I was incapable of being the person I thought I was supposed to be. I couldn’t be as generous, as unselfish, as loving without consideration of how it impacted me, because I have limits. I had to learn how to draw lines and create containers, work that was primarily about making money and work that was primarily about service. When I didn’t prioritize my own goals, my own needs, my own hurts, I was in a dark and painful place and hurt by people that I thought were more unselfish than they were.

In my spiritual life, as we are all expressions of God Hirself, I had to remember that my expression is of equal worth to every other person’s, and to prioritize my own joys and work as much as I served others.

Following this path has in some ways felt diminishing. I can say now that I have truly learned to love myself—as a practice, as a continual relationship of nurturing and care—and as I’ve learned that, my need for the validation and approval of others has diminished. But so too has been my drive to make a name for myself and be seen in public doing good works. I truly wonder whether the motivation to accomplish and succeed is proportional to the ferocity of one’s shame and self-loathing.

In the past couple weeks, I’ve been particularly present to a pattern of thinking that is consistently self-focused and angry and critical of others. There’s a sort of unhappiness with everyone and everything—I call it my “Aries Brain”—that seems to emerge from the basic and inescapable conflict between what I want and what is available. Even in the most beautiful place imaginable, floating in the ocean, meeting new people, there’s a part of me tallying all the minor discomforts, the failures of attunement, the disappointments.

It is exhausting. I think much of my childhood was spent avoiding this kind of thinking because it was too sinful, too selfish, and so I focused all that energy on being okay with whatever happened to me and caring more about other’s suffering than my own.

These habits of thinking I think are the polar edges of the focus between self and other. Disappointment, misattunement, minor conflict are all realities of being in this world. Even in the best relationships we have moments of miscuing and misconnection—one person wants to fuck and the other wants to cuddle; one moment we want encouragement and the other sympathy and our best friend offers the wrong one at the wrong time; we try to be allies but express our sentiments in a way that arouses suspicion and hostility instead.

Along with that, I find myself feeling more on the edges of my community again, mostly by choice and action. I’ve stepped out of leadership and gone quiet on issues that I know are still important but feel exhausted by all the times I’ve tried to speak on them and been ignored.

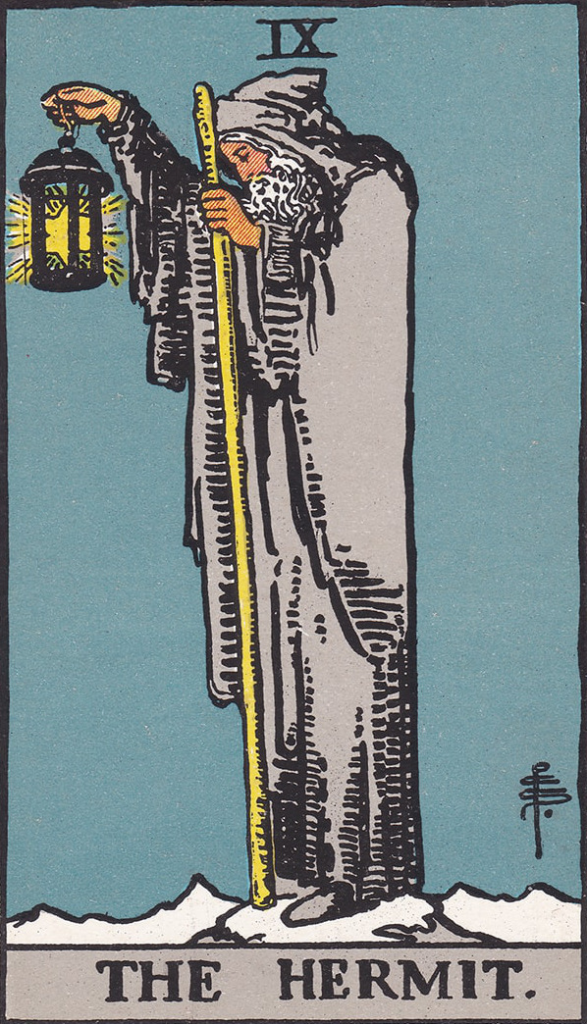

This past year of my life has been governed by The Hermit in Tarot-based numerology, a time of reflection and solitude but also a time of harnessing and distilling inner wisdom into the lantern that pierces the fog. In many Tarot decks, the Hermit carries this lantern that shines their insights as an invitation for those to follow rather than a demand for their attention. The Hermit also leans on a staff that has accrued all the hard-earned lessons and skills necessary to survive in this world.

As The Hermit, loving myself, I find my relationship to healing and spirituality is changing in ways that I’m not ready to declare in a definitive way. I see how much my healing journey and spiritual practice were rooted in a self-loathing and self-mistrust, an attitude of trying to eradicate my flaws so I could be okay. Now I see that I am okay and I am flawed, and there is nothing to fix, and that even illness is a part of me to love and include.

The Hermit’s staff also evokes the shepherd’s crook. I think of shepherding as a solitary activity, you alone with your flock for hours, not trying to do anything but keep them together and keep them safe. The journey of inner knowing and integration feels like the relationship between shepherd and flock. My job is not to punish, kill, or fix my parts. My job is to tend them, to witness them, to bring them together in connection and community. They are truly all doing the best they can, and they need the wise guidance of spirit and Self to grow beyond their limited perspectives and skill sets.

In that way, my practice feels much softer these days, much less ambitious, but still requires discipline. I still need to do the work of showing up and bringing presence into my life. Without presence, the lantern has no light.