3. We desire and fear presence.

I define presence as the experience of being in full awareness and acceptance of one’s immediate physical, emotional, spiritual, relational, and cognitive experience. In action, presence is simple. It is experiencing the present moment as it is. Engaged in life as it is unfolding. Connected to the environment and beings we are in relationship with and connected to the inner experience. This is in an aspirational capacity that most people do not have without effort and practice, but I think it is what we long for and forget we long for.

Experiences of grief and loss awaken us to this longing most acutely. When something or someone important to us is lost, we face the reality of death and the realization that we have not been wholly alive. We think of how much we missed out on, how we failed to savor the moments we had, how taking for granted the existence of these important people and experiences also meant allowing us not to be fully engaged.

This is one facet of the human condition. I might spend hours planning and preparing the perfect meal for the perfect dinner party, only to spend most of the evening caught up in my anxious thoughts and worries about whether the party is going well, whether the food is really okay or if people are pretending, whether people are having a good time. At the end of the night, I might realize that I did not actually attend my party. I forgot to savor it, and now it’s over.

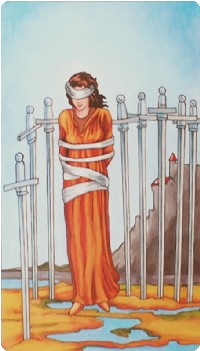

Mental, emotional, and behavioral problems intensify this struggle. People stuck in a deep depression are both disconnected from the moment because of their depression, and also struggle to find the motivation to become present, because being present means feeling exactly how poorly they feel. Anxiety pulls us out of the moment. Addictive behavior is in part a turning away from presence, chasing an experience that is only fleetingly glimpsed through substance or behavioral abuse and avoiding the raw immediacy of being.

Full presence also comes with a feeling of intimacy and vulnerability that might be painful for those unused to it. This reminds me of the moment in the Adam and Eve story in which they gain the knowledge of good and evil, and God wants to speak with them, but they feel ashamed because they are naked. One might read that as the dawning of conscious awareness, realizing that one is a human being among other conscious beings, seen exactly for who you are, unguarded, unprotected. Most of us want to run away from that. Most of us don’t want to see ourselves exactly as we are. And yet I believe we also have a deep longing for this, this experience that we try to describe through phrases like “being seen” or “being heard.” Both point to this experience of authentic, vulnerable connection in presence, witnessing and being witnessed. This state is in itself healing. Those parts of us that are fearful of rejection, criticism, and shame flourish when they are finally recognized within a state of full presence and acceptance.

Full presence also comes with a feeling of intimacy and vulnerability that might be painful for those unused to it. This reminds me of the moment in the Adam and Eve story in which they gain the knowledge of good and evil, and God wants to speak with them, but they feel ashamed because they are naked. One might read that as the dawning of conscious awareness, realizing that one is a human being among other conscious beings, seen exactly for who you are, unguarded, unprotected. Most of us want to run away from that. Most of us don’t want to see ourselves exactly as we are. And yet I believe we also have a deep longing for this, this experience that we try to describe through phrases like “being seen” or “being heard.” Both point to this experience of authentic, vulnerable connection in presence, witnessing and being witnessed. This state is in itself healing. Those parts of us that are fearful of rejection, criticism, and shame flourish when they are finally recognized within a state of full presence and acceptance.

Accessing states of presence happens to all of us in moments, but we need practice and diligence to really cultivate and expand them. Many religions offer such practices, whether that is the stated intention or not, to help people become more connected to the here-and-now and less imprisoned by habits of thought, feeling, and action. Psychotherapy offers its own tools and practices, in part by helping to name and dissolve the blocks in our personality that make presence so painful and challenging. Presence is also a modality of healing. Therapists offer this witnessing and presence to the client, who ideally begin to internalize this and develop their own capacities for self-witnessing and becoming present.