In Robert Sapolsky’s Behave, an impressive survey of studies and insights over years of research into human behavior and neurobiology, he reveals a curious and unexpected effect of oxytocin, the so-called “love hormone.”

Oxytocin is the name of the hormone our bodies generate when we’re experiencing loving connection. It is what helps us to feel that sense of bonding. Cuddling with a baby, a dog, a partner, a friend, all generate oxytocin.

We need and crave this oxytocin, in part because it helps us to make more effective use of the natural opioids in our system. The body produces opioids to both manage pain and increase feelings of ease and pleasure. Much of our pleasurable behaviors encourage our bodies to flood with opioids and dopamine, which we also crave. Without these opioids, we would be more sensitive to physical discomfort and ill at ease in life.

Evidence is suggesting that experiencing that opioid flood without oxytocin, or pleasure without loving bonds, means that we burn through the opioids faster and end up craving more and more for the same effect. Studies are indicating that the presence of oxytocin decreases the likelihood of developing tolerance and other behaviors associated with addiction.

In short, when we have loving social connections and regular cuddling, that improves our overall health and wellbeing and decreases the need for pleasure-seeking behaviors. When we share pleasurable behaviors with people we love, all the better.

So oxytocin is deeply needed, but what Sapolsky reveals is that it is also associated with increases in aggression and our bigotry. Surprise! You thought it was testosterone. Turns out, testosterone doesn’t necessarily make people more aggressive, it makes people more confident and assertive about their pre-existing tendencies. As Sapolsky says, if someone is inclined to be peacemaker, more testosterone will make them a more confident peacemaker. If someone is inclined to be an aggressive, coercive person, more testosterone will make them more willing to be that.

But holy shit, the revelation about oxytocin makes sense. Think of the deep bond between parents and children. Think of the wisdom about never getting between a mama bear and her cubs. When we love deeply, and bond with our loved ones, our need to protect them at all costs increases. We become fierce in staving off perceived threats to our people, our children, our beloved animals.

The important piece is “our.” Therein, I think, is the tendency for bigotry. Sapolsky discusses studies that show increases in oxytocin also increase antipathy toward whatever the person perceives as “Other.” As with testosterone, there does not appear to be an innate biological idea of what is “Other,” it depends on the person’s experiences of family and culture. It’s about what we define as “us” and “not-us.”

When I was a kid, I noticed how often kids would cluster into little cliques and form a sense of tribal identity. Not going so far as to create a name and a shared set of mythology and traditions—although some groups certainly had pieces of that—but you could get a clear sense of who was “in” and who was “out.”

But if you think about your own experiences with this, or your own noticing, you might think about how complex this “us” and “not-us” truly is. As kids, we were really cruel toward any kind of difference, especially in middle school. I was bullied as an outsider, and once I got my own group to be inside, I was cruel toward the outsiders of my group. We would find any kind of difference and mock it cruelly. I’m not going to name specifics of cruelty but neither would I sugarcoat it. We weren’t “woke.”

But it was inconsistent. If a kid was part of our crew but had an identifiable difference, that kid got teased—but if anyone else teased them then the whole crew became protective. In the movie Mean Girls there’s a lot of great examples of this, but the one that springs to mind is how two characters share a joke about one of them being “Too gay to function.” When that joke gets spread out among the school, she says, “That’s only okay when I say it!”

White people who get really confused about when it’s okay to say “the n-word” would intuitively understand why certain jokes and references are okay from loved ones but really offensive when coming from outside their group. That’s a normal human experience. We can be this way with each other because we share these bonding moments that give us a sense of loving connection. You are not part of our group so when you say it, it feels hostile at worst, unwelcome at best.

Thinking about all of this has brought me to some intriguing and troubling questions about bigotry, tribalism, and the emergence of Fascism.

The faces of white supremacy, patriarchy, homophobia, transphobia, fascism, dominionism—they’re all so friendly! With the unapologetic embrace of such oxytocin-fueled love and bigotry, these folks freely build families and networks that feel so accepting, so comforting, so friendly to those seeking connection and meaning in a rather isolating and dehumanizing world. At least, to those who are part of the “us.”

But then, the “us” contains its own tensions when the qualifications for inclusion are rigid and shaming. If your in-group has exacting expectations for behavior, appearance, and norms, and you do not fully match those, then the threat of social and physical violence looms under the surface. These expectations even extend to honorary “us”-es, people who do not actually match the qualifications but appear to accept their place in the hierarchies. White slave masters loved their slaves who outwardly appeared to embrace their roles, making them an honorary “us” but never completely “us.”

If we for whatever reason do not match the rigid expectations of being in-group, and are unwilling to accept the inferior place in the hierarchy, then we experience the threat of withholding of love, expulsion from the group, or violence. Staying silent and acquiescing leads to a slow psychic death, feeling like we are looking through the windows of a beautiful warm home while we stand freezing and hungry outside.

Speaking up and fighting leads to blistering displays of hostility and fear. The oxytocin bond is complicated for the rest of the “us”—if you aren’t fully in-group, if you are part of the family but also part of the out-group, then it would make sense that the protective fierce loving bond must also reckon with this—either by kicking out the threat or changing ideas about who is part of the group and who is other.

For those of us who do the work of unpacking bigotry and questioning these dynamics, however, struggle to include that deep bonding and sense of togetherness. We see ourselves as allies but not members of a collective community.

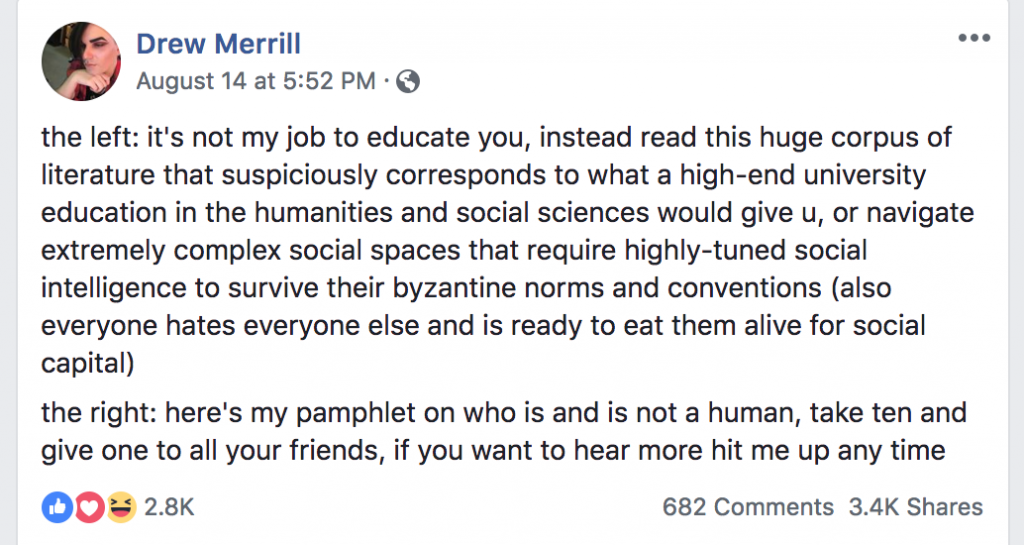

the left: it’s not my job to educate you, instead read this huge corpus of literature that suspiciously corresponds to what a high-end university education in the humanities and social sciences would give u, or navigate extremely complex social spaces that require highly-tuned social intelligence to survive their byzantine norms and conventions (also everyone hates everyone else and is ready to eat them alive for social capital)

the right: here’s my pamphlet on who is and is not a human, take ten and give one to all your friends, if you want to hear more hit me up any time

At a certain stage of racial identity development, for example, white anti-racists feel outside of the white communities that they find problematic, and also feel constantly on guard around each other and people of color. They might find community among white allies but even within that world there are often dynamics of social dominance and exclusion as white people aspire to “wokeness” and tear down anyone who is off the script.

Indeed, my observation is that “woke” white people can police each other more rigidly and with less forgiveness than most people of color would toward them. It is a way we carry our cultural legacy and wounding into our anti-racist work.

We struggle to define a tribal—for lack of a less problematic word—identity that would foster such deep love and acceptance. When we begin to feel ourselves coalescing into that kind of bond, then all those fears about inclusion and exclusion arise—as they must, I suspect, for any such bond necessarily excludes someone.

I remember the day that I noticed my sense of tribal affiliation was changing. I’d been working as a case manager for homeless folks and folks ensconced in the legal system—a relatively brief tenure in my career but one that continues to impact me. I was at the gym on the treadmill where one of the TVs played an episode of COPS.

As I watched, I saw a segment in which police officers approached a car where a man was sleeping behind the wheel. The cops woke up the man and demanded to know what he was doing, demanded he open his window. He took too long—by their reckoning—to respond, and then they pulled him out of the car and handcuffed him. He explained that he was having a fight with his partner and had taken some time to rest and work through it. The cop expressed sympathy but explained the guy was going to jail for the night.

I don’t know all the laws. I’ve never been a cop. But at no point in that vignette did anyone actually accuse him of committing a crime. At no point did he endanger anyone. He was sleeping in his car, and then he was arrested because he didn’t open his window fast enough. All of these behaviors are things I’ve done at some point in my life—driving off in a car, sitting quietly for some alone time.

I felt so angry on behalf of the man in the car. And then, in the next vignette, some cops similarly pulled over a man for no apparent reason, then he got out of the car and ran. I found myself cheering for him, hoping he’d get away. That’s when I knew things had changed. Once I would have viewed the police as protectors and these men as predators. After spending time being a case manager and supporter of men of color trying to navigate the legal system, my heart had bonded with them and begun to view the police as the out-group.

It’s difficult to detangle the emotional-hormonal instincts toward bonding and then the more intellectual, rational capacity to think according to laws and principles. Depending on where we stand, some blending of both will go into understanding the scenarios I discussed above.

We easily minimize or excuse the actions of those within the “us” and then exaggerate and vilify the actions of those who are “not-us”. We hear occasional stories of highly conservative, anti-abortion folks who secretly seek or pay for abortions. But their need for abortions are always special exceptions, which fail to elicit any kind of sympathy or understanding for anyone else who has the need. We also see those who are more liberal who might have sympathized when Obama and Clinton turned away refugee children from the border now apoplectic when a Republican oversees the same behavior. We rationalize our principles when they threaten our belonging.

Any kind of path forward toward a community of love and justice must contend with the craving for and shadows of that intense oxytocin connection. We need a sense of belonging and emotional safety. We truly need a shared sense of meaning and humanity to access the kinds of fierce connection and devotion that build strong communities of love. We need that sense to be accessible and intuitive, rooted in a shared symbology that speaks to our mythological natures.

The title is in part a reference to a song by Roisin Murphy, “Overpowered“