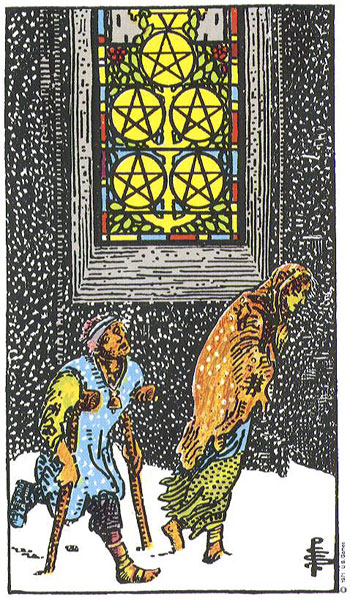

There are people sleeping outside in the cold and the rain. There are systemic, economic, cultural, and personal reasons for this reality, but in almost every large population this is happening. Someone gets excluded and needs to survive at the edges of others’ privilege. They knock, ask, and demand and get shut out. When I worked as a barista, I would pass them at 5 in the morning as I was walking to work—sheltering under whatever awnings were available, clustered together within a temporary fortress of boxes until someone came along and told them to leave. My next job has been, in part, to help these people find places to sleep, and I tell you the pickings are slim if you have no income, and even with a small income, the waitlists are long.

People who do not sleep on the streets do not always see what it’s like for a person to be homeless and poor every day. We see people begging or cajoling for money, eliciting whatever emotion works to get resources: humor, intimidation, pity. We barely see them if we can avoid it. Instead of providing funding for the housing that’s needed, our communities tend to make being poor and homeless a criminal act, punishable by cycling in and out of jail and back out to the streets without a job, without a place to sleep, with mounting legal debts that are unpayable.

Being poor and homeless is full-time work. For those trying to pull their way out of their condition, they constantly cycle between appointments and filling out paperwork. And waiting. Killing time. Finding community wherever it is. Most of us do not see this hustling and harassment, we only see what appears to be a life of indolence because this person is sitting on the street, doing things to get money. We feel superior because we are on our way to jobs where we sit or stand for hours, doing things to get money. For some, the poor and homeless are scary because we fear the harm they might cause, not recognizing how their harms can only be personal where we have access to systemic harms. This person can steal your wallet and the city can install fencing and spikes so that there is nowhere comfortable to sleep, and it does so in your name.

Being poor and homeless is full-time work. For those trying to pull their way out of their condition, they constantly cycle between appointments and filling out paperwork. And waiting. Killing time. Finding community wherever it is. Most of us do not see this hustling and harassment, we only see what appears to be a life of indolence because this person is sitting on the street, doing things to get money. We feel superior because we are on our way to jobs where we sit or stand for hours, doing things to get money. For some, the poor and homeless are scary because we fear the harm they might cause, not recognizing how their harms can only be personal where we have access to systemic harms. This person can steal your wallet and the city can install fencing and spikes so that there is nowhere comfortable to sleep, and it does so in your name.

The people who sleep on the streets are neither angels nor demons, but neither are we. We’re all inheritors of the same tangled human heart. Within us are the exiled people, the parts of us that we find offensive or ugly, who remind us of truths we’d rather ignore because they are too unsettling. Somewhere within each of us, something scrabbles for survival, something dwells only on its immediate pains and pleasures and cares nothing for the suffering of others. Each person’s pain is the largest pain they can carry, no matter what privilege supports them.

Generosity is what expands our capacity to hold pain and care at the same time. Generosity can begin by simply being real and confronting the truth of the moment. Instead of turning away from the uncomfortable reality, turning toward it, truly looking at it. Finding what is human that dwells beneath years of pain and trauma and making what offering is possible in the moment. Not giving into manipulation and scams, but offering what is truly needed and what you are capable of offering.