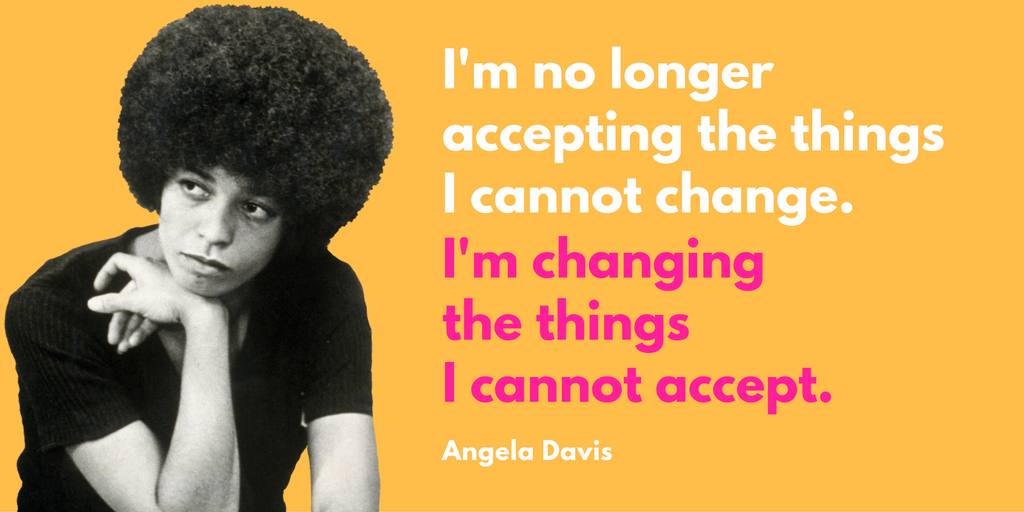

At New Year’s Eve 2016, I was at a friend’s house and noticed a book on the astrology of 2017. Some of us picked it up and looked it over, in conversation. From the author’s picture I had immediate (and inaccurate) judgments of the content, thinking it would be a relatively shallow New-Agey text. When I flipped open the book, the first thing I saw was this quote was this epigraph:

Holy shit, I thought. Even the nice white New Age lady is pissed off.

Earlier this year I was thinking about mental hygiene during a propaganda war, which continues to be a worthwhile practice and point of contemplation as the United States’s traditional arbiters of meaning have gone to war against each other and insurgent communities are using this opportunity to flood us with noise, misinformation, and seductively simple answers.

No matter how powerful anger makes us feel, it’s exhausting to be angry and guarded all the time. It’s exhausting to feel overwhelmed and powerless. And as life-transforming as it is to accept what we cannot change, there are times when it is also necessary to change what we cannot accept.*

When I feel the most cynical, despondent, and powerless, that’s when I know I need to get off my ass and do something important to me. If there’s a cause that matters, then I need to make the phone calls to the congresspeople, go to the city hall meeting, even symbolic gestures like lending material support to works I care about. Powerlessness is a significant feature of several mental health disorders, which can lead to a complete surrender of agency like a major depressive episode or, seemingly paradoxically, into destructive expressions of rage.

We are made to be heard and seen, to have an impact on our surroundings, and to belong to a community. These days, it is unfortunately all too easy to lack any of these experiences of connection and personal or social power. And people who have felt powerless or victimized—whether we think it’s warranted or not—are quick to jump onto self-righteousness and gleeful joy in others’ suffering should the balance of power abruptly shift.

None of this is particularly helpful in changing the things we cannot accept. Spite often relishes the conditions that cause it. People nourishing spite love being attacked and persecuted, even if they accuse others of being “victims,” because the high of feeling self-righteous feels more enticing than the vulnerability of acknowledging how one has been hurt and what one truly wants.

This is one of the reasons why I am a proponent of setting aside labels like “good” “bad” “positive” or “negative” for our feelings—fixating on the “good”-feeling feelings and avoiding the “bad”-feeling feelings can turn us into self-absorbed assholes. Whereas embracing the value of all of our feelings, and understanding that taking meaningful action might engender painful or “bad”-feeling feelings ultimately contributes to true personal power. Changing the things we cannot accept is rarely easy and without stress, but these are the experiences that draw upon the virtues of courage and resilience—the qualities we celebrate in our heroes.

* Discerning between the things we can and cannot change is a subject larger than the scope of a blog post. However, I do think they are complementary. As I learn the things about myself that I cannot change and must accept, so am I better able to accept these things in other people. Then my efforts toward changing what I cannot accept are more effective, as I’m wasting less energy on things out of my control.