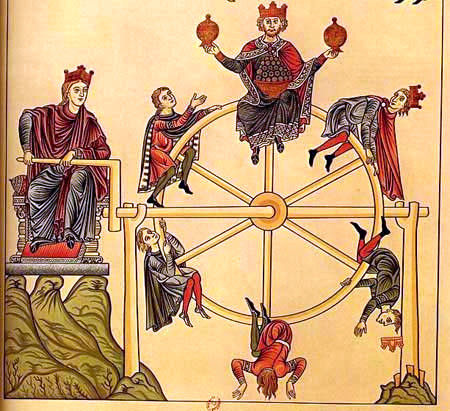

In Jung and Tarot: An Archetypal Journey, Sallie Nichols contemplated the tarot card The Wheel of Fortune in a way that has stayed with me for more than ten years. Nichols speaks of The Wheel as an image of human consciousness in various stages of evolution and Self-possession.

In the early stages of consciousness, we are at the edge of The Wheel. Our emotional reactions to life events “ride” us. We’re lifted high into the air and then slammed into the ground and run over. At the mercy of our emotions, we are even further at the mercy of life and the people around us who elicit the emotions. We cannot separate our awareness of self from the emotional reaction, we have no power, no choice in how we respond.

Nichols’s metaphor of spiritual growth is consciousness’s movement from edge to the center of the Wheel. In the center, we continue to spin, but the spinning is less violent. We are better able to watch the movements from a distance. We can watch ourselves spin around the Wheel but instead of lashing out or shutting down, we can try something different. In a sense, we see that we cannot control the Wheel of emotions and life circumstances but we can control how we engage with them.

Spiritual and contemplative practice help us to become more aware of this process. We see the cycle of emotion. We begin to see how we can take ownership of our emotional cycles, instead of blaming others for our feelings.

This is a spiritual growth that does not involve negating what is painful. It is a growth that teaches us how to move back into center when we find we’re at the edge of reactivity. Too many people have shame at having feelings at all, thinking that spiritual enlightenment means being an emotionless being that has transcended human vulnerability.

If that’s true, I’m not there yet. What my observation is, and what I have learned from the greatest Teachers of my life, is that spiritual growth means those emotions, passions, and reactions have more room to simply be themselves, to give their purest response, to alert me to their needs.

I can feel the emotional reaction, watch myself going through the old cycles of blame and defensiveness, and all the while some part of me sits quietly in the center, knowing that it’s all bullshit. The emotion is valid, but the stories of blame often aren’t. Some part of me may say, very urgently, “They’ll be so mad at me!” and feel all the terror and guilt of disappointing someone else, and meanwhile in that still center there is that knowing. Perhaps it’s, “No, they won’t.” Or sometimes it’s even, “If they are, it is okay. They have a right to be angry.”

To shift the metaphor slightly, I see the trajectory of psychospiritual growth as both moving consciousness to the center of the wheel and, ideally, putting that centered consciousness in the driver’s seat. That entire sentence looks straightforward but getting there could take years of work, with growth and setbacks.

Some days, the best I can do is to be in my emotional reaction and conscious of the part of me that knows it will be okay. That part of me might be able to blunt my most toxic responses or impulsive decisions. Some days I lose it entirely and make hurtful mistakes, but with practice and self-compassion those instances grow further and further apart.

Even still there is a part of me that feels a “should,” that I “should” be able to move out of the painful experience into joyful enthusiasm. And some days I can. Other days, I need to practice the best I can with what I’ve got.