Author: Anthony Rella

-

The Tyranny of Positivity

Although I am passionate about mental health and believe a life well-lived is benefitted by generous portions of gratitude and remembering what is sweet in life, I believe the cultural injunction to “keep a positive attitude” is at best irksome and at worst toxic. Barbara Ehrenreich offers an interesting social, political, and economic critique of the power of positive thinking, but I want to focus on mental health and growth. -

Knowing You Are Enough

Lately, I and several brilliant thinkers I am lucky to encounter have been discussing the idea of being “enough.” Some of us experience a sense of vulnerability around the idea that we’re not enough, or that we’re too much.

- I’m not smart enough, attractive enough. I’m not a good enough lover. I don’t have enough money.

- I’m too emotional, too damaged, too ugly, too stupid.

These experiences of deflation or inflation suggest that some part of us gets identified with this quality of being inadequate, somehow wrong, somehow not quite compatible or capable of satisfying our wants and needs. (more…)

-

Fire Climax Pines

During one of my attempts gardening, a friend explained to me that regular pruning can help plants to thrive, even when its branches were not already withering. He told me stories of fruit farmers taking heavy chains to beat trees, the stress of which would cause the trees to respond with more life energy, becoming hardier and generating fuller fruits. I’ve heard about “fire climax pines” who reproduce only after burning. Given my difficulty at keeping plants alive, I took more insight than practical accomplishment from this information.

These examples suggest to me that some capacities emerge only in response to adversity. Episodes of chaos and challenge confront us with what does not work, what is lacking in resilience. The converse is also true, as we discover what solid ground supports us, what truly endures. When facing adversity, we could abandon what is no longer useful and dedicate energy to what is resilient, potentially enriching life.

When suffering, some folks tend to close up and withdraw; others become angry and hostile; others dramatically perform pain; still others behave as though everything is fine while inside feeling a sense of desperation and collapse. These strategies can all serve as forms of denying the truth of what is happening inside and outside by fixating on one tendency, one facet of experience. Denial can be a life-saving coping mechanism when used judiciously. Denial is problematic when it is our only tool and we do not realize we’re using it.

Prescribed Burn Near Beaver Village, Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge, by Shannon Nelson When we prevent ourselves from facing the anxiety of the challenge, however, we lose an opportunity to respond creatively. Crises can precipitate a time of great growth and renewal in personal, spiritual, and systemic development. Long-standing structures of belief and habit that blocked growth give way, making energy available for new forms.

(I recommend not saying this or anything like it to someone sharing fresh pain and grief with you. Messages like “How can you make the best of this?” or “This will lead to better things” can be experienced as cruel, dismissive, and potentially as blaming the suffering person. I’ve done it. You’ve probably done it. Quashing that urge is hard, but try! If you are fortunate enough to not be in the midst of a crisis and talking to someone who is, I recommend starting with simple empathy and offers of help. Later, when the person is ready, you can start talking about meaning and growth.)

We do not need to rush into this kind of change and growth. Those alarms going off inside are worthy of attention and respect, though not necessarily obedience. We can give ourselves time to avoid and freak out. We also need to give ourselves time to feel the pain and disruption of the challenge. We can also give ourselves time to check inside and ask, “What is it that I want for myself? What kind of life or system do I want to create?” I often need to remind myself of this. We do not need to know how to get there. In fact, it’s better to not cling too tightly to any one solution when in the middle of a crisis. What helps is simply to orient the inner compass toward the life we desire and try to connect to the hope that you will get through this crisis and thrive.

-

Help and Power

At some point in life, everyone needs help, and almost everyone gets an opportunity to offer it. Another thing humans like to do is build identities around certain aspects of our personalities, such as: the person in charge, the person who helps, the person who gives; or others being the person who is lost, the person who is helpless, the person who needs. If these opposing identities meet each other in different persons, this perfect match can quickly lead to toxicity, blame, resentment, and disempowerment. (If we can find these opposing qualities in ourselves, we can become more whole, more free, more resilient.)

Let’s look at our attitudes toward giving and receiving help. Toward the end of this article, Shauna Aura Knight offers an example of the boss who attempted to give her a task, and when she asked clarifying questions, impatiently took the taskback and said he’d do it himself. I’ve been that person on both sides of the exchange. When I worked as a barista, we did high volumes and expected a lot out of each other. We also grappled with periods of high turnover, when trained employees left and untrained employees entered. Those of us who were trained and used to operating at a particular level of performance could get highly stressed by the feeling that we had to pick up the slack, maintain our usual level of service, and deal with the honest mistakes and ignorance of a new employee. It could get very difficult to patiently explain how to make a drink with a new employee when there was a line of customers out the door and a backlog of drinks. Sometimes the best choice was to simply put the employee in a position they could manage while a more experienced worker pushed through the rush.

-

On Indignation

Something about indignation is enticing. Where there is a group of people, particularly an institution, there are pockets of indignation, complaining, and gossip. Groups within the group form, sometimes around a core of mutual disdain for a particular person or policy. When groups become too insulated, and feed on their indignation, they can stoke each others’ feelings of persecution, warranted or not.

Shared complaining has value. It can bring cohesion to a group and healing to its members. As a person who tends to think problems are in my mind, I can feel enormously relieved to discover that others share my concerns. Feeling included in a person’s confidence, to share their problems and secrets, can inspire feelings of self-worth, however temporary. These conversations can be opportunities to relieve emotional pressure, identify shared problems, and start to work toward solutions. Gossip can protect potential victims from abuses that are not otherwise being addressed, or transmit information that affects many people, although the information becomes quickly diluted, changed, and separated from the facts.

(more…) -

Odes to Time

To Linear Time

Blessings on you, highway

between birth and death

upon which experience

can flower and wither.

Finite currency, ever-depleting

account, the hoarding

of which bankrupts,

the wise spending

of which enriches.

Through you we receive

the gifts of variety,

multiplicity of sensation,

feeling and thought,

the complex textures

of Being offered to life.Through you we learn

the powers of ending,

discernment, and priority,

savoring what already

is becoming lost.

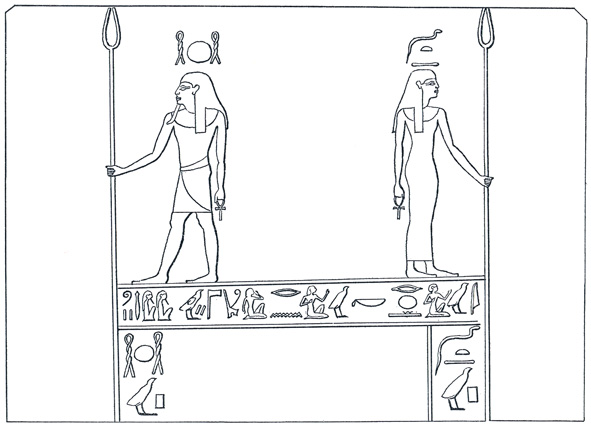

Neheh and Djet, sometimes translated as “Time” and “Eternity” To Cyclical Time

Praise to you, spiral galaxy

interlocking orbits

recurrence of season

and history reminding

us nothing is complete,

only refreshing its form.

Through you forgotten

lessons are relearned:

the old births the new,

the new restores the old.

Depth of meaning,

unfathomable purpose

rotating and shifting,

unfolding patterns

informing the cosmos.

Our eyes constellate

disparate stars, touching

every consciousness

that perceived a shape.

Each moment contains

eternal expanse. -

We Can Do Better

This post breaks from my usual psycho-spiritual explorations of Self to addressing a material, social reality: the problem of incarceration in the United States of America. According to 11 Facts about America’s Prison Population, the current prison population has quadrupled since 1980, and a significant portion of that population are nonviolent drug offenders. Per Human Rights Watch:

“While accounting for only 13 percent of the US population, African Americans represent 28.4 percent of all arrests. According to Bureau of Justice Statistics approximately 3.1 percent of African American men, 1.3 percent of Latino men, and 0.5 percent of white men are in prison. Because they are disproportionately likely to have criminal records, members of racial and ethnic minorities are more likely than whites to experience stigma and legal discrimination in employment, housing, education, public benefits, jury service, and the right to vote.

Whites, African Americans, and Latinos have comparable rates of drug use but are arrested and prosecuted for drug offenses at vastly different rates. African Americans are arrested for drug offenses, including possession, at three times the rate of white men.” [Emphasis added.]

Incarceration is one step in a cycle. People with criminal records are released from prison without income, without guaranteed housing, without guaranteed jobs, without substantively better skills and resources, and often with increased trauma as a result of their imprisonment. They get dropped back into the world and expected to participate in a culture that actively stigmatizes them. Criminal activity might be the only survival skill they know, the only skill available. Families and communities are decimated by the cycle of incarceration and recidivism. People in higher socioeconomic classes might have more resources to buffer these losses. For people in lower socioeconomic classes, these consequences can be catastrophic.

The war against drugs has eroded our civil liberties and significantly harmed people of color. Building and staffing prisons has become a for-profit enterprise that costs states $21,000-33,000 per year. We would do more to stabilize our communities if we spent that money on housing and services for offenders. Incarcerating offenders in violent, repressive systems with other offenders does not promote social wellness. Even Newt Gingrich called our prison system “graduate schools in criminality.”

This is not about eschewing justice and ignoring the harm done. This is about how Justice as a value and civic virtue has twisted against our better nature to perpetuate systems of social inequality, and how fear and systemic racism continue to feed off each other. When we focus on punishing offenders more than creating healthy, resilient communities, we perpetuate cycles of injustice, poverty, and racism. We can do better than this. Organizations already exist that are attempting to create societies without prisons. Even if you do not endorse the complete abolition of prisons, we need their voices to find some better way.

-

If you need to hear it:

You are not broken.

-

On Practice and Change

For almost seven years I have committed to a daily meditation practice. Some days I am only able to manage a few minutes, other days I sit for a half hour. I go through minutes or weeks in which during meditation my mind wanders to television shows I recently watched, conversations recently had, things I want for myself, things I worry about, anything but attention to what is happening in the present. Recently I sat, after a long period, and became aware of an exquisite sense of discomfort and attention to the dark blankness that lay behind my eyelids. An acute sense of boredom came upon me.

“Ugh, I’m stuck in here with myself.”

The practice of sitting still and focusing on breath or observing myself sounds simple, but simple is not easy. A lot of the problems people create for ourselves seems to come from our resistance to simplicity. We have to train ourselves to become simple, which requires a surprising level of complexity. Every time the mind wanders from the practice, we have to invite our attention back again and again. We develop skills of will, self-observation, delaying gratification, enduring discomfort, emotional self-management, these complex subroutines that contribute to moments of stillness and inner silence that deepen and expand into rich presence.

Any skill worth cultivating requires such practice. When beginning a practice, we might be tempted to compare our clumsy first steps to the elegant performance of a master, but again any master has put in time and discipline to reach such grace and simplicity. Hours of practice forge that appearance of effortlessness.

From the Golden Tarot by Kat Black To change ourselves requires such practice, discipline, and self-forgiveness. There may always be a part of me that feels disgusted with myself, that would rather be anywhere but in this body, in this life, but there is another part of me that knows sitting with all of this helps me to connect with something greater than the individual pieces, greater than the momentary discomfort, greater even than the self-loathing. Spiritual traditions point toward these greater realities and advocate practices and values to help people grow into them.

Making any change in our lives means confronting the ambivalence that keeps us stuck. Ambivalence is different from indifference, though often we use them interchangeably. Indifference means not caring at all, one way or the other. Ambivalence means caring very strongly in two opposing directions. “I really want to meditate this morning, and I really want to hit snooze and get more sleep.” No matter how often I go to the gym and value the benefits of regular exercise, a part of me wants to convince me that I’m not feeling up to the task and would be better served eating chocolate and resting on the couch.

Resistance will meet whatever it is we need to make our lives better — taking medication, going to therapy, reaching out to loved ones, eating well. That resistance is what helps us to become stronger. We do not develop muscle or aerobic health without pushing against a physical resistance. Our bodies and spirits need something to push against, and they also need time to rest. Too much of one or too little of the other both create problems. Ambivalence points toward the need to recognize these conflicting impulses and strive to find some way to honor both.

If I want to know myself, love myself, and be the most myself I can be, I need to sit with the part of me that gets bored, hates myself, and criticizes all my flaws. I need to practice bringing my attention back to the more that is happening now. There is always more than this problem, whatever problem holds your attention. There is always another breath to take. There is the firm support of the ground and the expansiveness of the sky.

Changing one’s self requires accepting one’s self as we are now. Worthwhile, deep, profound change comes from taking on a discipline and returning to it regardless of how one feels. It’s hard to exercise four times a week, but the benefits of maintaining that rhythm are healthier and longer-lasting than what comes from taking short cuts to force one’s body into a socially acceptable shape. This kind of discipline is imperfect. After seven years, my mind still wanders in meditation, and I forget to bring it back. Seven years is truly not that long, but the person I have become in that time has depended upon that foundation of cultivating inner stillness and self-observation.

-

Advice for a New Year

Ignore perfect answers.

Perfect, instead, mistakes.

Befriend and tend your shame,

that nuzzling beaten pup

whimpering through thin bars,

mutt tongue licking your heart.

Notice the traps you set

For friends and enemies

To prove trustworthiness

Again. Watch as they fail,

disappointed to your

expectations, or spend

your strength to help them win.

No problem having problems.

No worrying worry,

no fearing future fear.

Try hoping hopefully,

enjoying joyfully.

My father gave advice

About taking advice:

“Just say ‘Thank you,’ and do

whatever you want to.”