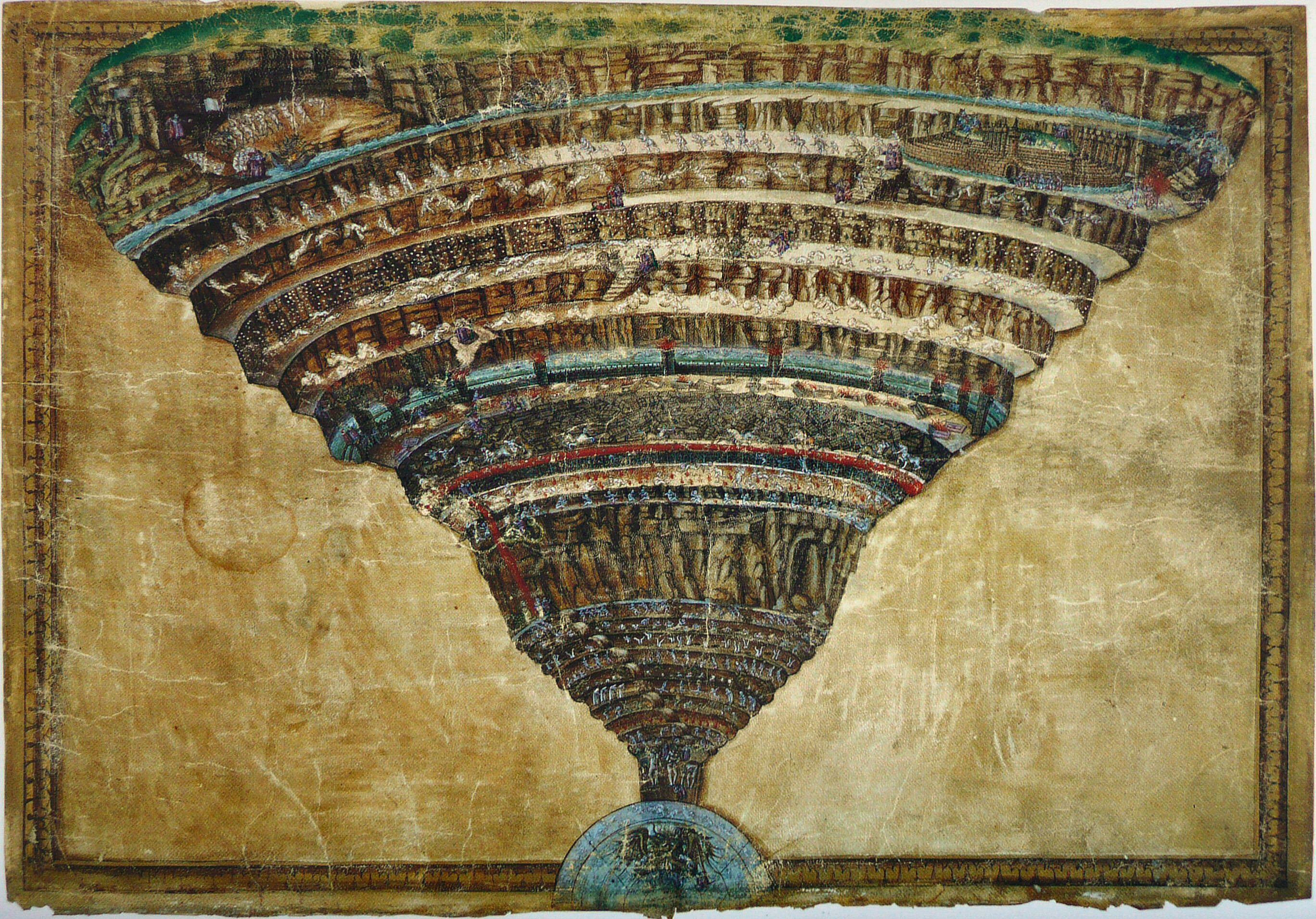

In Dante’s Divine Comedy, the protagonist must descend all the way through the nadir of Hell before he can begin to climb toward Heaven. In terms of Dante’s Christianity, the journey suggests that coming into knowledge of one’s sinful nature creates the possibility to transform and shed those sinful habits, via Purgatory, before finally ascending into Heaven. This geographical and poetic mystery evokes, for me, one process of psychological healing. Fully healing and transforming our suffering requires a descent, a conscious immersion into the pain and every layer deeper until finally emerging into its resolution. To me, this is depth psychology.

My tendency, historically, has been to withdraw and watch. If I felt I could be invisible and simply watch, I could notice all kinds of things about a group, a person, a situation, and offer great insight. What was terrifying to me was taking action and being emotionally present. I was an intellectual-based person with no sense of my emotions or my body. I used to “joke” that I had no feelings, and with this lack of feelings was a heavy depression. My mind could understand and argue many things, but when it came time to take action or put it into practice, I would balk. What I needed to become whole was my heart and my body. To manage my anxiety, I took up smoking cigarettes. I was in college and dealing with all new kinds of stresses and anxieties, both socially and academically. Because I felt so uncomfortable at parties having spontaneous interactions with people, I preferred to go outside and have a cigarette with a smaller group of folks.

Here is where unhealthy coping strategies compound suffering. We have the core pain—my anxiety at being in social situations with others. If I had a therapist at the time and some better strategies, I could have begun to learn being with my anxiety and my ambivalence about intimacy, sink more deeply into the experience, and find ways to connect. Instead I avoided my anxiety through smoking and added more problems—reduced lung capacity, smelly fingers and clothes, a money-draining habit, and the potential for long-term health problems. Smoking became my go-to habit when I felt upset or anxious, and I got anxious a lot. I also kept myself from adventures and new friends, as my smoking buddies tended were usually the same from event to event. They were absolutely wonderful people and dear friends, but after a while it seemed there was no point in going to a party of strangers if I was not meeting new people.

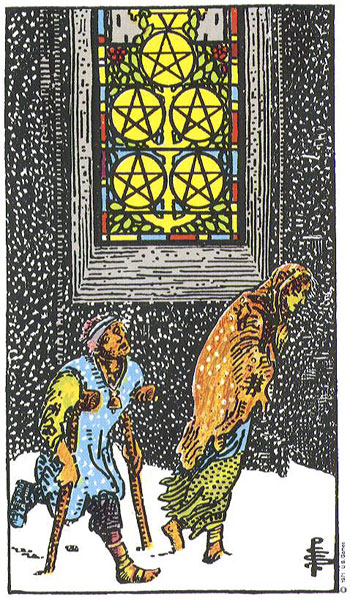

This is how our automatic and unconscious habits become what I think of as “Devil’s bargains.” In many stories, a deal with a devil figure usually means one gets a short-term gain at a huge long-term cost. Smoking cigarettes helps avoid the feeling of anxiety now, but the anxiety remains, and the economic and health costs add up. In college, a dear friend introduced me to a track called “I Might Fall” by the band Fetish. In the lyrics, the singer says, “To be free from the pain / you have to be free from the painkiller.”

To step away from the painkiller is to begin the healing descent through Hell. For people who continue to avoid their inner work, this descent manifests as “hitting rock bottom,” reaching that point where they no longer can avoid or deny the costs of their habits. For those willing to engage, this descent into Hell is a conscious work of healing. We work to let go of the numbing agents and feel our true feelings. Dante’s protagonist had a guide, Virgil, who knew the ways of Hell and loved the protagonist well enough to steer him through. Guides might appear as a sponsor, a therapist, a spiritual mentor, or a trusted friend who knows the ways, but such guidance is invaluable.

When we let go of these patterns and begin to feel the pain we’ve been avoiding, we might feel insane. “Why the hell am I doing this?” What helps me is to connect with my core desire—to be joyful, to be present in my life, to be loving and connected to others. Going into my pain, examining myself, and beginning to name what harms me gathers power within. Discomfort, slowly, lessens as we learn to be more at home within ourselves. We convert our unprocessed pain and stuck feelings into something more fluid, energy we can use to live, not just survive. Pain stops being something terrible to be avoided at all costs. It simply becomes one more texture of emotion, one we can experience with the rest. We can tolerate more life, we can learn to embrace it gladly. We find our way through the forest into the great open plain of possibility.

Being poor and homeless is full-time work. For those trying to pull their way out of their condition, they constantly cycle between appointments and filling out paperwork. And waiting. Killing time. Finding community wherever it is. Most of us do not see this hustling and harassment, we only see what appears to be a life of indolence because this person is sitting on the street, doing things to get money. We feel superior because we are on our way to jobs where we sit or stand for hours, doing things to get money. For some, the poor and homeless are scary because we fear the harm they might cause, not recognizing how their harms can only be personal where we have access to systemic harms. This person can steal your wallet and the city can install fencing and spikes so that there is nowhere comfortable to sleep, and it does so in your name.

Being poor and homeless is full-time work. For those trying to pull their way out of their condition, they constantly cycle between appointments and filling out paperwork. And waiting. Killing time. Finding community wherever it is. Most of us do not see this hustling and harassment, we only see what appears to be a life of indolence because this person is sitting on the street, doing things to get money. We feel superior because we are on our way to jobs where we sit or stand for hours, doing things to get money. For some, the poor and homeless are scary because we fear the harm they might cause, not recognizing how their harms can only be personal where we have access to systemic harms. This person can steal your wallet and the city can install fencing and spikes so that there is nowhere comfortable to sleep, and it does so in your name.