Since becoming a mental health counselor, I’ve had a number of conversations with people who aren’t my clients that vary around a particular theme. “I like my therapist, but …”

The “but” is often that the therapist is missing something important that’s going on for the client. “I realize I bullshit them for a whole hour.” “We talk about what’s going well but not [significant problem].”

In these conversations, I have hesitantly wondered whether they’ve discussed this with their therapist. I’m hesitant because the question seems so obvious as to be offensive, and I’m not wishing to come across as blaming the client. But I do find that, often, the answer is no.

The “no” is for many reasons, all of which are perfectly valid, and most of which are getting in the way of therapeutic progress. There is a power differential—the therapist is supposed to be the one who sees clearly, the one who knows what’s going on. A client may feel sheepish about correcting or challenging their therapists (not all, believe me, but it happens). A client may feel scared of what could happen, if the therapist will respond well or respond in a damaging way.

Often these inhibitions resemble our relationships with other authorities, or with our parents. It’s vulnerable to challenge an authority figure directly—far easier to go to a friend or acquaintance and complain.

A client may also be unfamiliar with how the psychotherapeutic conversation differs from an everyday conversation. They want to spare their clinicians’ feelings. They may want their therapist’s approval and respect, and feel reluctant to expose vulnerable or complicated emotions. They may not trust their therapists.

Another possibility is that the client, and perhaps the client and therapist both, are hesitant to broach a potentially explosive topic. Perhaps both sense intuitively that more time and trust building is needed before opening up these difficult experiences. Perhaps one, the other, or both are simply avoiding the topic. Perhaps one, the other, or both simply can’t see the topic.

A particular acquaintance of mine reflected that often after therapy they would realize they “bullshitted” their therapist for the full hour and felt concerned that the therapist didn’t notice. My question was, “When do you recognize that you’re bullshitting your therapist? How long will you let yourself continue to do so?”

Occasionally we hear of stories of that perfect therapeutic moment, where one’s therapist sees clearly and put words to something the client didn’t even know they felt until it was named. Those moments are really special, and I bet that same therapist has a good amount of hours under their belt where they missed the mark—possibly even with that same client.

Many of these patterns are our defensive social patterns playing out in the therapeutic room. They are the behaviors that keep our pain and struggles locked in place. We deeply want to be seen, and we deeply fear being seen. The therapeutic relationship is the perfect opportunity to try something different.

Say shit to your therapists. When you realize you’re avoiding, bullshitting, not talking about something important. Bring it up. Bring up the fact that there’s something to bring up and you’re afraid to bring it up. Whatever you feel able to do. It’s vulnerable, and there’s a risk, so be gentle with yourself. Your therapist ideally is creating with you a relationship that is safe enough for you to step out of your comfort zone. They can’t force you out of it.

These kinds of issues and conflicts are important, and having a conversation about it can help you and your therapist break through into a deeper and more effective working relationship.

Or you might discover that your therapist isn’t the right fit for you—they respond poorly, or they continue to engage in avoidance or denial. Then you might consider saying something like, “I’m going to find a better fit.”

If you enjoyed this post and want to support the writer, as well as get access to content before it goes public, you can become a patron at his Patreon.

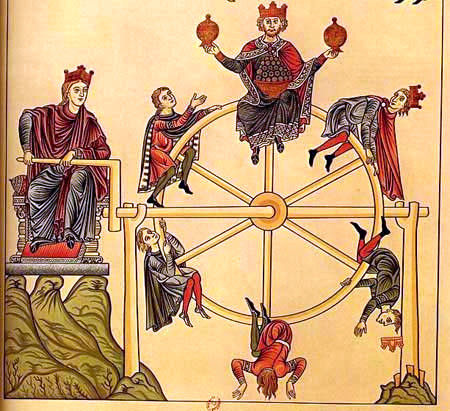

In addition, you may preorder my book, Circling the Star.