During the long isolation of COVID-19’s first year, I noticed my mind become foggy and soft-edged. I fumbled with words and lost interest in most intellectual debates. At times I would be in mid-sentence and realize I’d lost the path to the end, and it would take long moments to recall what I meant to say.

The prospect of losing my mental faculties used to terrify me. As a kid without much physical prowess or social acumen, I gambled all my worth on intellect and the realm of the mind. To be the one who knew, the one with the sharpest and most decisive argument, were my positions of power. In the shadow of that power were all the moments of forgetfulness, ignorance, and incompetence—great horrors I tried to conceal from others.

My greatest fears were around losing my mind. Who would I be without my intellect and smartness? And though COVID brain is not nearly so severe as dementia or other cognitive disorders, these clear lapses in capacity might once have compelled me to begin some ridiculous daily routine of mental exercises to stave off forgetfulness.

Instead, I noticed myself feeling unbothered by my forgetting, and slightly relieved to realize I no longer worried about how smart I was. Sharing this with others, I’d say, “I’m not sure if this is maturity or decline.”

Commonly, the wise people in my life would say, ”Maybe it’s both.”

“No!” I’d protest, with futility. “It can’t be both!”

But of course it could be both. Maturation is a process of gain and loss. As we lose, for example, the energy and resilience of youth, we gain greater wisdom and efficacy. I’m thinking of an uncle who spent much of his life doing construction on houses. The last time I saw him was with a cousin my age, and a friend of my cousin’s who worked on projects with my uncle. The friend kept going on about how my uncle would take more breaks during their work, but he’d also accomplish more and work longer than both of them. What he may have lost in terms of energy, he’d gained in skill and efficacy.

Seeking is Lacking

What I’ve been gaining in my work is a greater sense of self-acceptance and the capacity to accept, acknowledge, and nurture all of my parts. And with that has come a decrease in the need to be the smartest guy in the room, to “prove myself” of having worth, and particularly to seek the approval of others.

That word, seek, carries a heavy burden. Our words for desire, both “want” and “need,” are rooted in a sense of lacking. Seeking implies an outward gaze, a searching for approval from a place of not having it. When I’d seek validation or approval from others, and didn’t get it, I would be thrown into a storm of self-doubt and frustration. In a state of seeking, moreover, the people who did validate and approve of me seemed less important than those who had not yet, or withheld approval.

What feels increasingly true for me is to expect validation and approval from the people most important to me in life. This isn’t to say I refuse criticism, concern, or disapproval. But in conflict and love I practice trying to understand how a person came to their position, and I look for the points they make that do seem valid and worth acknowledging.

This never means I think their entire framing and context is valid. For example, I’ve listened to folks raise concerns about vaccinations and found one or two points where I’ve thought, “That’s fair. I get why you’d be worried about that.” Those are the places where we can dialogue, but I’m not going to follow them into the wild speculations of their bizarre anti-Semitic conspiracy theories.

Acknowledging what’s valid in another person’s perspective doesn’t weaken my own. People have a tendency to mirror what they’re receiving: when they feel genuinely heard and understood, they’re more willing to offer that in return. When they feel dismissed and belittled, they give it right back.

But I’ve also learned that there are times when a person feels heard and understood but still doesn’t make the effort to listen to my perspective. When I would let this rile me up, I gave too much ground in compromise, trying to placate them rather than insist I be treated with equal respect.

These days I am willing to offer validation but I also expect it in return. When in a conversation with a person who seems unable or unwilling to make effort in understanding what’s valid in my perspective, I waste less of my time trying to persuade them. Nothing about the urge to get them to understand me right now serves either of us. More and more, I acknowledge the impasse and say I need a break for both of us to chill out and reflect.

When I seek validation, I imagine a posture of leaning forward, reaching out, beginning to lose my balance in the effort to connect and be seen. When I expect validation, I feel myself leaning back into the support of my heels, grounded and centered, letting the other person move further away or closer.

Two Fish Swimming Apart But Tethered Together

In a sense, the seeking of approval and validation reveals a polarization within the Self. One part of me is afraid of being bad, worthless, wrong, stupid, or whatever harsh and shaming words apply to your particular constellation of fear. Another part wants to get away from this bad feeling by seeking the validation of my worthiness or goodness. Since my inner state is one of badness, the seeking feels that approval must come from outside myself.

Yet these two parts—the shame and the seeking—are like two fish, tethered together but swimming in opposite directions. When one pulls, the other pulls. The very act of seeking approval stirs up that part that believes I am not already “good,” who pulls back in terror that its “badness” will be seen. Perhaps, for a time, we find a stable situation in which we’re able to maintain a state of approval and feeling “good,” but that “bad” feeling thrashes under the surface, in anxiety dreams or moments of emotional overwhelm when we have a bad day.

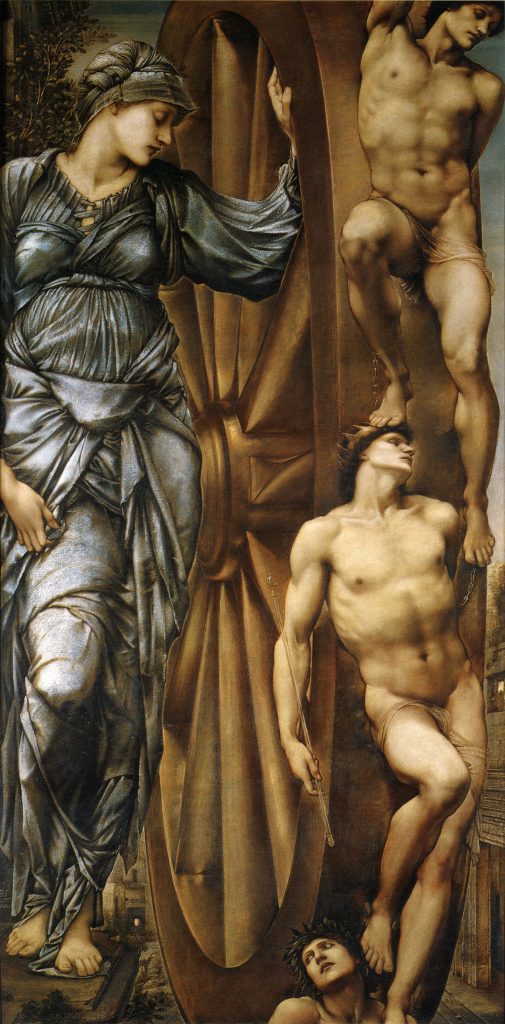

The problem of “the pairs of opposites” in human psychology show up in so many spiritual and psychological traditions, particularly those in the Daoist, Buddhist, Hindu, and Jungian traditions. In my own Neopagan spiritual tradition, we speak of the Divine Twins as gods who embody of this fundamental tendency toward polarization.

Our perception and relationship with these Twins changes based on where we are in our psychospiritual process of awareness and maturation. When we think of ourselves as only singular, only one thing, we cannot accept the Twins within, and they are at war. We seek to identify with one of the Twins and cast the other out of ourselves into the world.

In this state, we often stay at the level of “good” and “bad.” Whatever I want to be is “good” and what I don’t want to be is “bad.” Some of us may identify with this goodness and see badness in the world; others of us may feel the other way around, seeing themselves as awful and others as virtuous and lovable.

For example, I often identified as a peacemaker, someone who tends toward harmony and compromise. In college, when my friends and I would sit around discussing which fictional characters we were, or what our superpowers would be, we said that my power was “anti-drama.” I had a tendency to be a peacemaker, to bring down the temperature of conflict.

Within this story is an implicit judgment of “drama” as self-evidently silly, irrational, and undesirable. Like I was this aloof, elevated being who has no time for the petty drama of other people. And that judgment also turned inward, dismissing my own hurts, angers, and upsets as petty, irrational, and insignificant.

Judgment is such an interesting phenomenon, because so many of us fear it while constantly enacting it on other people. My greatest fear was sharing why I was mad or hurt and someone else dismissing me as being a “drama queen”—making a big deal out of a small, silly, petty problem. So my judging parts became the gatekeeper of what was serious and what was dramatic. But in its protectiveness, it became zealous, and kept too much of my hurt stored in my inner world, and my relationships became more distant and robotic.

Conflict avoidance and peacemaking is a survival strategy I inherited and leaned on to navigate my unique life challenges. With such a rigid inner gatekeeper, I experienced a great deal of suffering and problems that could’ve been avoided by being direct and honest about my feelings. But parts of me were terrified of what could happen if I disappointed, angered, or hurt others.

Along with this was a tendency—which I now view as a compulsion—to involve myself in others’ conflicts—to mediate, not to take sides—while avoiding fighting my own battles. When I sensed the slightest bit of tension between others I noticed an urge to intervene, to lighten the mood, to explain what I think is going on, or to make apologies or excuses for others. At times, this is helpful—it can reduce tension and increase harmony, especially if I as a third party notice that conflict is coming from a miscommunication that’s easy to rectify. “I think what she meant to say is…”

Yet often it seemed to make the conflict bigger and more entrenched. At my most immature, I would talk one on one with people and try to make excuses for the other person, or share with one person why the other was upset. All this did was make people more distressed and angry, and interfered with the two people working out the conflict together. More and more I wonder if I created conflict out of what was merely tension.

Jung spoke of this as “enantiodroma,” the tendency for a thing to become its opposite, which he learned from Daoist thinking. For me, too much peacemaking and suppression of conflict actually stirred up drama. Imagining how a drama queen could become a peacemaker, I remember people in my life who had no problem bringing up grievances and slights when it affected them, but met my own hurts with a calm, dismissive, “Let’s put the past behind us.”

“The Peacemaker” and “The Drama Queen” now seem less to me like separate complexes and more two polarities of the same energy. When we think of polarization in terms of magnets, you may know from experience that trying to push together the same polarity on two magnets causes them to resist each other with increasing force, while opposing polarities come together with great intensity. When we identify with one end of a polarity, we may draw the opposing polarities out of others, and come together in a stable if too rigid embrace.

Only when we can hold both ends of the polarity within do we become free of the dance of attraction and repulsion. Or, rather, our dancing with polarities becomes freer. We can flip from one to the other, attracting or repelling at will. Meeting drama with drama might, indeed, work better for some of us. To take care of myself emotionally, to set boundaries, to make relationships work, I need to get a little dramatic, to get into conflict, and be a little messy while we work through our differences to see if we can establish a better harmony.

Increasingly these pairs of opposites seem less like antagonists and more two allies with different perspectives that can help us to find and walk the middle way. The Peacemaker becomes the part of me that values harmony, collaboration, and building relationships of mutual value. The Drama Queen becomes the part of me that cares about my own hurt and confusion and knows the only way to clarify these issues is through speaking up.

Often I think of a Buddhist story in which a student says to their teacher, “Master, sometimes I am confused by your teachings. When I come to you some days, you give me guidance that seems to contradict what you’ve said on other days.” The Master responds, “Imagine that you are walking along a narrow bridge, blindfolded, and drunk. When you start stumbling to the left, you risk falling off, so I shout out, ‘Go right!’ Then you stumble to the right, and risk falling off that side, so I shout, ‘Go left!’”

When we can witness our contradictions with equanimity, they become our own wise masters who keep us on the bridge. Should I move too much toward one, the other is there to call me back.

Non-Striving

Another teaching of these polarizations is that whatever posture we take toward the world is answered. Being too identified with the Peacemaker, I felt both overwhelmed by the extent of conflict in the world and a covert sense of superiority, like I was the only one mature enough to handle these conflicts. This superiority was condescending and disempowering toward others. I’ve never enjoyed people who treat me as incapable of handling my own problems. And it’s a trick that keeps me in this mindset that somehow I am responsible for other peoples’ problems. Not only does this guarantee endless, exhausting labor, it deprives others of the opportunities to work through their conflicts and discover the powers of self-advocacy and intimacy.

Stepping out of this idea that this world is a place that must be fixed, saved, or acted upon—this white savior fantasy of myself—has been liberating and brought with it a kind of cynicism. What is progress if every movement forward creates new problems and resistance? What is conservation if every restriction draws out resistance and rebellion?

Which brings me back to the weary teachings in the first chapter of Ecclesiastes, which I first read as a child:

All streams flow into the sea,

Translation via Biblegateway

yet the sea is never full.

To the place the streams come from,

there they return again.

All things are wearisome,

more than one can say.

The eye never has enough of seeing,

nor the ear its fill of hearing.

What has been will be again,

what has been done will be done again;

there is nothing new under the sun.

Is there anything of which one can say,

“Look! This is something new”?

It was here already, long ago;

it was here before our time.

No one remembers the former generations,

and even those yet to come

will not be remembered

by those who follow them.

Certain experiences seem cyclical, fated, and ongoing in this world. Much of life is spent in hunger and desire, seeking to satiate those longings. Even when we do succeed in feeding those hungers, inevitably we crave more, or a new desire emerges.

No change is free of creating new complications. We gain new functions and possibilities while losing others. To imagine we can create a lasting, permanent, original change feels grandiose and inflating, which then plummets us into despair and hopelessness when we fail.

Yet stepping out of that grandiosity helps us reconnect with real power and vitality. Helping one person we know feels ennobling and gratifying. Solving all suffering is impossible. But solving specific problems is a fascinating experience. My Peacemaker imagined if he could simply help everyone calm down and work out their conflicts, he could rest, which made him resent conflict. But if it’s okay for there to be conflict—if conflict itself is not a problem that demands my constant effort—then I can rest deeply, and I can engage in what feels interesting or meaningful to me.

Is this maturation or decline? All along, whether people think I’m good or bad, I simply am. My needs exist whether I squash them for peace or raise them up like a burning torch and demand everyone pay attention. What has always felt most healing is presence, witnessing, and compassion. Finding that capacity within me that is neither polarity but able to contain and witness the both, with fondness. There is nothing to win, nothing to prove, nothing to fix. There is effort without effortfulness, action without striving, listening without passivity. Only the understanding that liberates and shows us the path of our greatest wholeness.

There is nothing to win, nothing to prove, nothing to fix.

There is effort without effortfulness, action without striving, listening without passivity.

Only the understanding that liberates and shows us the path of our greatest wholeness.