Last December I was out running errands with my spouse. We noticed a man standing on an island in the middle of traffic holding up a sign on which was written one word, a hashtag. I had no idea what to make of it. “What on earth is he doing? What is the point?” I looked up the hashtag on my phone, learned about a conspiracy theory that seemed pulled straight from the 1990s “Satanic Panic” playbook, and told my spouse about it. My spouse, in turn, pointed out that I had done exactly what the man with the sign wanted. He infected with this meme, this idea. Not too long after that, the hashtag and its associated story motivated a person to go into a business named in the theory with a gun, threatening the workers.

We are in the midst of a war for our minds. More accurately, as Rhyd Wildermuth writes, we are waking up to a war that has been ongoing. Different factions seek to influence our behavior through seeding our minds with ideas in line with their interests. When it’s an influence I don’t like, I want to call it propaganda. Alley Valkyrie discusses why, and why this is limiting, in her column “Musings on Propaganda in an Age of Authoritarianism”:

We tend to interpret the word ‘propaganda’ as information that is inherently untrustworthy. We refer to “Soviet propaganda” or “anarchist propaganda” with the understanding that those folks likely aren’t telling the ‘truth.’

Historically, propaganda was generally regarded as a neutral force, holding true to its Latin roots. ‘Propaganda’ derives from propagare, meaning ‘to propagate,’ and propaganda was recognized as a powerful weapon that could be wielded in the name of countless agendas. It was only with the rise … of authoritarian governments that disseminated mass propaganda through the means of mechanical reproduction in order to manipulate the public in favor of repressive tendencies, that the word took on a permanently negative connotation.

Once upon a time, I believed that most conflict and bigotry arose because people were not adequately aware of “the truth.” If I could simply, calmly, and rationally explain that truth to another person, I thought, they would understand my perspective and change their behavior. This is a fantasy underlying many forms of liberal activism, from fighting climate change through racial justice, among other causes.

In this worldview, there are arbiters of truth, at least those who come closest to understanding our best grasp of the truth. It is appalling, according to this mindset, that anyone would ignore or deny these arbiters of truth, such as the scientists who affirm that climate change is real and human behavior is causing it. When confronted with that, the response is often to become condescending, dismissive, all the hallmarks of “liberal elitism.”

Now this fantasy seems facile. What is lacking is appreciation for another truth. It turns out rational argument is not enough, there must be a compelling appeal to the heart as well. Marketers and public relations professionals have known this for decades.

During my late teens, I read William S. Burroughs’s essay “The Electronic Revolution”, in which the writer Burroughs discusses human language as a literal virus (a concept that has become mainstreamed in our reference to content “going viral”), and ways by which language becomes weaponized and used in the service of those societal twins, control and subversion. “Illusion is a revolutionary weapon,” he asserted, going on to explore strategies of employing doctored recordings to plant seeds of doubt and rebellion.

Here’s one example:

TO SPREAD RUMORS

Put ten operators with carefully prepared recordings out at rush hour and see how quick the words get around. People don’t know where they heard it but they heard it.

Social media today attests to his theories. I’m scrolling through my news feed and see a provocative headline that suggests something that wants to appeal to my most Id-centered emotions: anger, fear, pleasure, vindictiveness. I see that someone I don’t like got “DESTROYED” on a news show, or a politician got caught out on a scandal that had been long-suspected (or desired). Sometimes I click on the article and, upon reading, realize that the headline is misleading or the story is actually much less compelling than promised.

Other times, it gets its hooks in me. When the topic comes up in conversation, I’m already half-assuming it’s true. “I heard that! I saw it online.” People make a trending hashtag about it, memes about it. I get into arguments over why it matters. I argue about the way people argue about it. Several people write thinkpieces on why we’re misunderstanding the essential reason why the news matters. Maybe I learn later that the story was misleading but the damage is already done.

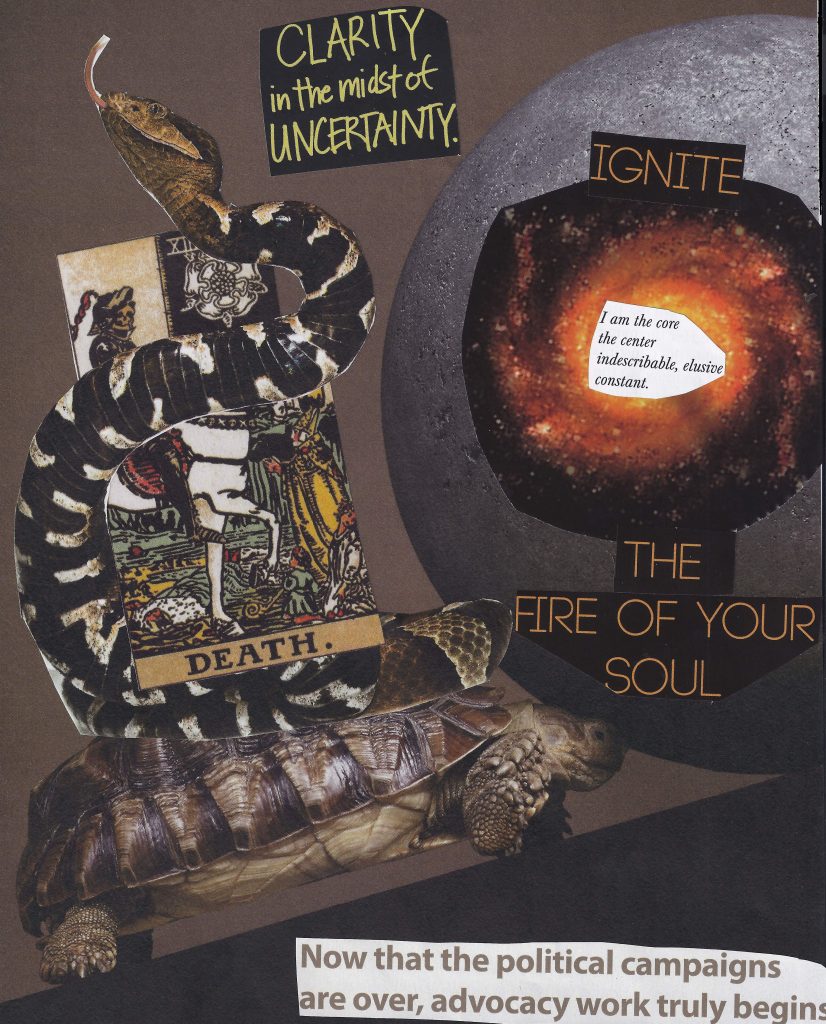

For those who still value the idea of transcendent, liberating truth, the idea of a war of propaganda is offensive. Sitting with my own discomfort, I take Valkyrie’s point that propaganda is a neutral technology, one that could successfully broadcast one’s own beliefs and opinions as much as opposing ideologies. Memes, for example, are effective at persuasion and consolidation of bubbles because they appeal to both lobes of the brain. They contain language communicating the essential point (left brain) with aesthetically and emotionally captivating images (right brain).

“The Electronic Revolution” was a significant influence on the industrial music scene, which played with the splicing of musical forms with sampled audio content. One of my favorite exemplars of the genre is Meat Beat Manifesto’s Satyricon, a work that explores themes of propaganda, state control, and liberation of the mind through freeing the body. The song “Brainwashed This Way / Zombie / That Shirt” is a triptych that splices and remixes media samples from advertising, film, and political speech over a series of shifting beats to link together marketing and the deployment of pleasure for social control. (I cannot find an officially sanctioned version of the song available online, but a YouTube search will get you there. Or you could buy the album.)

All this said, while a wholly rational appeal is not very effective to motivate change, a wholly emotional and aesthetic appeal is dangerous. Appeals to fear, anger, and pleasure are very effective at getting us to turn off our critical thinking skills. This feature is beyond political orientation.

So what could help us keep our heads on straight in a “post-truth” world? I’ve got some ideas in this next post.